Sitting at work - the cost to business & what to do about it

Image source: Smart Work

What's the problem?

Only 66% of men and 58% of women in England say they do the recommended amount of physical activity1. Even this may be an overestimate when compared to actual activity levels measured using activity trackers2. 27% of adults do less than 30 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity weekly and are classified as ‘inactive’3 People also sit a lot. Men in the UK spend an average of 78 days a year sitting during the day; for women, it’s 74 days a year4. Activity trackers show that office workers spend up to 71% of their working day sitting down, and those who are most inactive at work are also the most inactive out of working hours.5

What's the impact?

Evidence shows that people who sit a lot are at a much higher risk of ill health than those who don’t. There is ‘conclusive and overwhelming’ scientific evidence for physical inactivity as a primary cause of 35 chronic diseases6.

People who spend a lot of time sitting are more likely to suffer from a whole range of physical and mental health issues including: musculoskeletal issues, reduced cognitive function (worse memory, less able to solve problems and think creatively), Type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke, vulnerability to infections, depression and anxiety, feeling fatigued and lower overall quality of life.

What's the solution?

Conversely – and as you might expect - physical activity has been shown to strengthen our immune system7, lower risk of heart disease, high blood pressure and diabetes7, as well as dementia, various cancers and stroke, while improving mental wellbeing and reducing anxiety and depression8. 9.

More surprisingly perhaps, the greatest benefits occur when people who are very inactive move even just a little more. The evidence is clear that although more exercise is better, any physical activity is good. The many benefits can start at even the lowest levels.10 The new UK physical activity guidelines are pragmatic and recommend that all individuals should be encouraged to ‘start their journey’ to a more active life by doing what they can and making small changes such as getting off the bus a stop early and walking the rest of the way10. In fact, the greatest risk reductions are experienced by the most unfit when they increase their activity by only a small amount11.

Even just replacing 1 hour of sitting a day with low-level activity like household chores, gardening, mowing the lawn, or walking, can reduce mortality by 30%.12 Interventions that focus on being more active, even just breaking up sitting time, especially among older people and office workers, have been shown to be effective at reducing health risks13, 14. Research shows that there are a number of strategies incorporating self-monitoring/prompting technologies which both employers and employees think are realistic ways to help them sit less15, 16. See, for example the work that Melitta McNarry and her team have done for the GetAMoveOn Network, testing the Rise and Recharge! app in workplace settings. It is possible to reduce sitting time even in challenging environments like call centres where employees are typically very desk-bound if programmes are carefully designed17.

What's the benefit?

The good news is that if employers take steps to encourage employees to sit less and move more - even just a bit - during their working day, they can expect staff to feel:

• Less back pain

• Less neck pain

• Less stressed

• Less anxious

• Less depressed

And to be:

• More energised

• More focused

• More productive

• More engaged

Who wouldn't want that?

What's the cost of doing nothing?

An estimated 6.9 million working days are lost in the UK due to work-related musculoskeletal problems18 and the cost of poor mental health to UK business is estimated to be an astonishing £35bn annually19 so encouraging employees to move more could translate into significant cost reductions and productivity gains.

How do I take action and where do I begin?

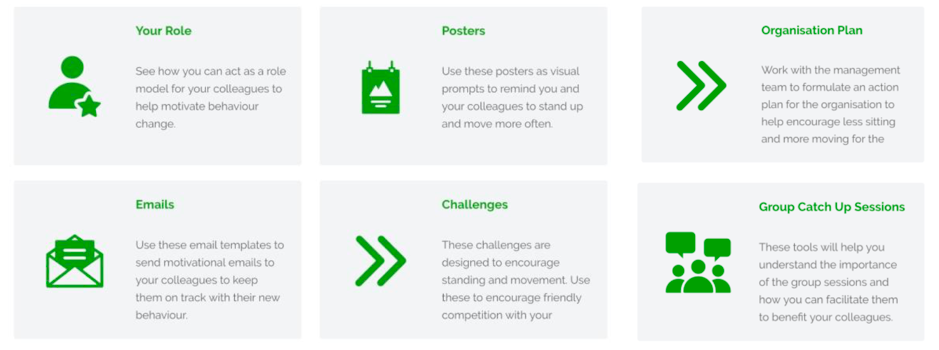

SMART Work is a proven programme with a free resource kit to help organisations encourage and enable employees to sit less and move more, and so create a more dynamic workplace. There are also resources for individuals to help them change their own behaviour, and for workplace wellbeing champions to help them run effective move-more initiatives at work.

The programme and resources were developed by a team of researchers from the University of Leicester and have been tried and tested in a research project in real workplaces. The research shows that their approach works and can save organisations money.

So what are you waiting for?

Find out more and sign up for your free toolkits

References

1 NHS Digital. Health Survey for England, 2016. digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2016

2 Harris T et al (2019) How do we get adults and older adults to do more physical activity and is it worth it? Br J Cardiol 2019;26:8–9 bjcardio.co.uk/2019/02/how-do-we-get-adults-and-older-adults-to-do-more-physical-activity-and-is-it-worth-it

3 NHS Digital, Lifestyles Team (2019) NHS Health Survey for England 2018, Health and Social Care Information Centre digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2018

4 British Heart Foundation. Physical Inactivity Report 2017 - [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Aug 30]. Available from: bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017

5 Clemes S et al (2014) Office Workers' Objectively Measured Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity During and Outside Working Hours Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 56(3):298–303 insights.ovid.com/pubmed

6. Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol 2012; 2(2): 1143-1211

7. Nieman DC, Wentz LM. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. J Sport Heal Sci [Internet]. 2019 May 1 [cited 2019 Aug 8];8(3):201–17. Available from: sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S20952546183010058.

8. Allender S, Foster C, Scarborough P, Rayner M. The burden of physical activity-related ill health in the UK. J Epidemiol Community Health [Internet]. 2007 Apr 1 [cited 2015 Dec 30];61(4):344–8. Available from: jech.bmj.com/content/61/4/344.full9. Knapen J, Vancampfort D, Moriën Y, Marchal Y.

9. Exercise therapy improves both mental and physical health in patients with major depression. Disabil Rehabil [Internet]. 2015 Jul 31 [cited 2019 Aug 8];37(16):1490–5. Available from: tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09638288.2014.972579

10. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines 2019 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf

11. McKinney et al (2016) The health benefits of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness BCMJ, vol 58 no 3 p131-137 bcmj.org/articles/health-benefits-physical-activity-and-cardiorespiratory-fitness

12. Matthews, C. E., et al. (2015). Mortality Benefits for Replacing Sitting Time with Different Physical Activities. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 47.9, 1833-40. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25628179.

13. Kazakos K, Bourlai T, Fujiki Y, Levine J, Pavlidis I. NEAT-o-Games. In: Proceedings of the 10th international conference on Human computer interaction with mobile devices and services - MobileHCI ’08 [Internet]. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press; 2008 [cited 2019 Aug 13]. p. 515. Available from: portal.acm.org/citation.cfm

14. Stephenson A, McDonough SM, Murphy MH, Nugent CD, Mair JL. Using computer, mobile and wearable technology enhanced interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. 2017 Dec 11 [cited 2019 Mar 29];14(1):105. Available from: ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12966-017-0561-4

15. Stephenson A (2019) Reducing sedentary behaviour in the workplace: using digital health technology pure.ulster.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/76437712/2019StephensonAPhD.pdf

16. getamoveon.ac.uk/media/pages/events/symposium-2017/3551716348-1563382476/gamo-symposium-booklet.pdf

17. Morris AS, Murphy RC, Shepherd SO, Healy GN, Edwardson CL, Graves LEF. A multi-component intervention to sit less and move more in a contact centre setting: a feasibility study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):292. Published 2019 Mar 12. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6615-6

18. Health and Safety Executive (2019) Work related musculoskeletal disorder statistics (WRMSDs) in Great Britain, 2019 hse.gov.uk/statistics/causdis/msd.pdf

19. Michael Parsonage and Geena Saini (2017) Mental health at work: the business case 10 years on, Centre for Mental Health centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/mental-health-work-business-costs-ten-years